Yvon Chouinard is an outdoors guy — surfing, fly-fishing, rock climbing. The riskier the better.

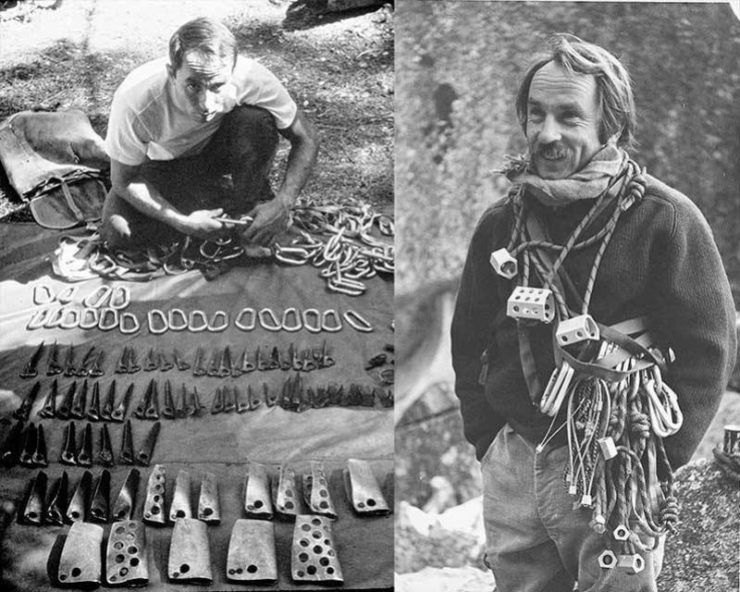

To finance his hard-scrabble lifestyle, he taught himself blacksmithing in order to design and make climbing tools for friends. Before he knew it, Chouinard was a leading manufacturer of climbing equipment in North America. Soon, the kid from Maine who dreamed of being a fur trapper like his French-Canadian forebears had become what he did not want to be: a successful businessman. On a trip to England with his future wife, Malinda, they discovered a small factory that made clothing from vintage corduroy. Chouinard fashioned heavy-duty shorts and shirts suitable for climbing, adding a clothing line to their climbing equipment. Their company, Patagonia, was born.

Since they began Patagonia in 1973, the Chouinards have always run their company with a deep concern for the environment in which their products would be worn and used. They designate one percent of their annual sales to grassroots activists working to protect the environment and combat climate change. They were among the first companies to use sustainable materials and insist on fair labour practices and just wages from their suppliers. The firm’s marketing campaigns focus on asking people to buy only what they need — the company famously ran an ad on Black Friday with the headline, “Don’t Buy This Jacket.” Today, Patagonia is valued at $3 billion.

Now 83, Yvon Chouinard is looking to the future. He wants the values of Patagonia to continue. So he gave away the company.

The reluctant billionaire who’d rather go mountain climbing or fly fishing than manage his business, with the full support of his wife and family, has transferred ownership of Patagonia to an irrevocable trust and non-profit organization to ensure that Patagonia’s profits — some $100 million a year — will be used to combat climate change and protect undeveloped land around the globe. Patagonia will continue to operate as a private, for-profit company, selling more than $1 billion worth of jackets, hats and ski pants each year — but the Chouinards no longer own it. The trust is irrevocable — the Chouinards can’t take the company back. And that’s how Yvon Chouinard wants it.

“I didn’t know what to do with the company because I didn’t ever want a company,” Chouinard explains. “I didn’t want to be a businessman. Now I could die tomorrow and the company is going to continue doing the right thing for the next 50 years, and I don’t have to be around . . . “Despite its immensity,” Yvon Chouinard says, “the Earth’s resources are not infinite, and it’s clear we’ve exceeded its limits.”

While our lifestyles change and adapt because of the development of new technologies and advances in science and medicine, the values of our lives themselves remain constant. The good people at Patagonia realize that and have taken extraordinary steps to make sure their company is more than a profitable company but a socially responsible one, continuing to contribute to the care of the environment. Jesus calls us to that same challenge: to embrace the Gospel spirit of gratitude and generosity that continues to grace the world long after our temples of materialism and consumerism crumble; our “assets” of compassion and justice will hold their value well beyond the time when the far lesser things for which we have leveraged our lives prove empty and valueless. In his Christ, God calls us to seek much more precious and lasting gifts than this world is capable of offering — treasures like compassion, reconciliation, justice, peace. What is required first, however, is to give up the avarice that makes possessing the things of God impossible.